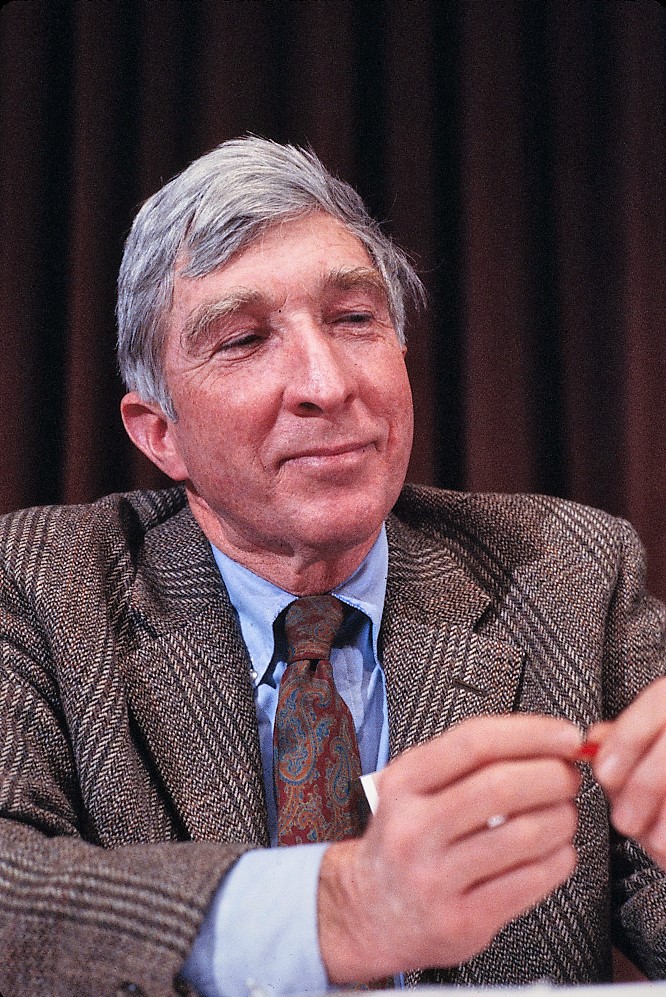

John Updike never disappoints. Anytime I pick up his books, I am mesmerised by the beauty of his prose. I don’t read him for his plots, his pace; his novels are to be lingered over and savoured for their vivid images and sensory details. He is a sensuous writer whose ability to evoke the senses is perfectly complemented by his recurring themes of love or marriage. Depicting couples with his gift for describing people and places, he instantly transports me to America, for that is what he portrays to perfection. Though he wrote about other places, too, like rock and roll, country music and Elvis Presley, he is authentic Americana.

One of Updike’s greatest strengths lies in his portrayal of relationships, particularly those between couples. His treatment of love, desire, and conflict in marriage is tender yet unflinching, capturing both fidelity and infidelity. In Rabbit, Run and its sequels, Updike delves deeply into the heart of Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom’s life, capturing all the acts and emotions — love, affection, betrayal, estrangement, regret, reunion and loss — that humanity has to experience. Through the lens of Rabbit’s relationships, Updike sheds light on the fragility and beauty of human connection.

In his Rabbit novels, Updike also paints a vivid portrait of American life, particularly in the post-war suburban landscape. These books are not just about the personal struggles of one man but also serve as a microcosm of American society during the second half of the 20th century. The changing social, political, and cultural landscape of America is reflected in Rabbit’s journey through life, his attempts to escape and reconnect, and his struggles with identity, religion, and the pressures of modernity. The suburban world Updike depicts is a place where the American dream is as much a burden as it is an aspiration.

Ultimately, Updike’s sensuous prose, coupled with his portrayal of relationships and American life, makes his work deeply resonant. His characters are not just figures on a page but living, breathing people. In the Rabbit series, Updike captured a moment in American history and culture with such vividness and depth that the books remain as timeless as they are intimate.

There is more to Updike than “Rabbit” Angstrom. He was already an established writer with a novel and a poetry collection to his credit before his first Rabbit novel—Rabbit, Run—was published in 1960. The Harvard graduate with a degree in English was already a regular on The New Yorker magazine, where he started as a Talk of the Town writer and became a book reviewer.

I just happened to dip into Due Considerations, a collection of his essays and book reviews, many of which first appeared in The New Yorker.

Updike being Updike, of course, he is mesmeric, as usual. I can’t resist quoting from his preface, where he writes about how his youthful yearning set him up to be a writer in the 1950s, when books, newspapers and magazines thrived and writers could be celebrities. Here’s Updike, romancing the 1950s as a writer-friendly era:

The pieces gathered here, in my sixth such volume since Assorted Prose (1965), are end-products of an adolescent yearning to become a professional writer, or at least to enter in some guise into the mass of printed material that hung above the middle-browed middle class in the middle of the last century like a vast cloud gently raining ink. There were newspapers, both morning and afternoon, and magazines, printed on shiny paper like Collier’s and Life or on duller stock like Scribner’s or Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

As an office boy at the Reading (Pa.) Eagle, I saw how men in green eyeshades called down a clattering hail of brass matrices at their tall Linotype machines. I saw how comic strips arrived as bundled cardboard intaglios, of the same pulpy substance as egg cartons, which were flooded with hot lead and blended into curved plates clamped onto thunderously spinning rotary presses that hurled news and amusement to the far corners of diamond-shaped Berks County.

Somewhere, in some manner, whether by wielding a pen precariously loaded with India ink or by pounding at keys that dented the inked ribbon of a typewriter, the boy I was sought to work his way into publication and a wider distribution than was afforded by what the scowling elders of his community called an “honest” job.

In that still-industrial era, there were tweedy exemplars, depicted in whiskey ads and on the cover of weekly journals like The Saturday Review of Literature, of The Professional Writer-Hemingway, Steinbeck, Thornton Wilder, Sinclair Lewis, Pearl Buck…

Television was soon to eclipse print’s inky cloud with its magnetic flare of electrons, pulling millions from their reading chairs to the viewing couch. The older electric media, radio and the movies, coexisted more peaceably with the literary world.Movies were visited for a secluded two hours and then left behind with the empty Good & Plenty box, and the radio demanded only a corner of your attention-you could read a comic book as you listened. Robert Benchley for a time had his own radio show and was a sort of movie star. The Algonquin Round Table was an off-Broadway show in continual performance, it seemed. But by the time, in 1955, that I got to New York, with a professional perch on the eighteenth floor of 25 West Forty-third Street, and a steel desk and a daily replenished supply of sharp pencils, the Round Table was cultural history and Benchley had imbibed himself to death, his long-planned tome on the reign of Queen Anne never written. A particular party was over…

In my naive picture of the American economy, a writer developed certain verbal skills and produced certain saleable artifacts-“literary products,” as my tax accountant annually states on the top line of Schedule C. The writer existed on an edge of his society from which its operations could be observed at his leisure, and he or she didn’t stray beyond that edge into hostility, exile, and isolation.

The dark side of modernism was just a rumor to me, though I had read The Waste Land in the Reading Public Library and dipped into the opening pages of Ulysses, much as one wades barefoot, in June, into the still icy Atlantic and quickly retreats with aching ankles and a virtuous sense of initiation. The English department of Harvard College immersed me in an ocean of written classics, and when, six years after my graduation, I became a book reviewer, I was still wet behind the ears. Up to 1960, I had made my living selling short stories and light verse, for which there was a significant but fickle and possibly fading market.

Reviewing books for The New Yorker was a way of maintaining a financial inflow, and getting into print, and keeping abreast, unsystematically, of what was happening in the fabled, embattled world of letters. There was something impure and even treacherous, I was warned, about a “creative” writer dealing in literary judgment and theory, but I brashly believed that I could protect the frail creator inside me from the bullying critic.

For nearly two years in the mid-Fifties I had worked cheerfully on The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town section, accepting the assignments that came down to me. To read a book and write about it was a task I could carry out far from the city, in exurban New England, where I had settled in hope of consorting with Americans more representative and relaxed than Manhattanites. A book review, in the spacious magazine that William Shawn edited back then, should be, said, “something more” —an essay of sorts, with personal and humorous riffs allowed. He believed in assigning nonfiction books to non-experts in the concerned field, and I versatilely qualified as a non-expert in almost everything.Writing a book review felt physically close to writing a story —same blank paper inserted in the rubbery typewriter platen, same rat-tat-tat sound of impatient, inspired x-ing out. There was a similar need for a punchy beginning, a clinching ending, and a misty stretch in between that would connect the two. A review writer was generally safe-safe from rejection (though it could happen), and safe, as a judge himself, from judgment, though an occasional reader mailed in a correction or a complaint.

The reviewer’s services, in a world overwhelmed by books, loomed as patently necessary: to weed, to cull, to impose order upon profusion. The aim of art is to make a virtue of necessity. Two aesthetic impulses vividly experienced in my childhood go into a volume like this one: the collecting instinct, that delights in sets of things, and the wish to arrive, through small improvements, at a final form.

The improvements are not all the author’s: most of the texts collected here benefited from the zealous scrutiny of The New Yorker’s checking department, and from the sensitive ear and grammatical scruples of editor Ann Goldstein. My editor at Knopf, Judith Jones, and copyeditor Terry Zaroff-Evans contributed their own refinements.

Updike’s humility and generosity are evident in his acknowledgment of the editors who refined his work.